Southern Steelhead Trout

Steelhead trout (Onchorhyncus mykiss) are remarkable in their ability to adapt to fluctuations in stream flows, sediment input and water temperatures, enabling them to survive despite the occurrence of temporarily unfavorable conditions. Southern steelhead have evolved behavior patterns that permit them to compensate for the fluctuations in Southern California coastal streams and rivers. While they will return to their natal (stream of birth) stream to spawn, they can utilize other streams when the natal stream is not available (i.e., sand bar not breached, lack of water). Also, steelhead can become resident trout if water conditions preclude them from migrating to the ocean.

Endangered Status

The southern steelhead was listed as endangered by the National Marine Fisheries Service in 1997. The southern steelhead Endangered Species Unit extends from San Luis Obispo County to Malibu Creek, Los Angeles County. On July 1, 2002 the southern boundary will be extended all the way to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Life Cycle

Life Cycle

Like other salmonids, steelhead must leave the ocean and enter freshwater to spawn. Starting with the winter rains, steelhead will enter the large coastal streams, making their way to good habitat (abundance of gravel, clean, well oxygenated water, abundance of insects) in smaller creeks and tributaries. The female deposits her eggs in a small depression in the gravel, where the male fertilizes them. After 100 days or so, the small fish (called “fry”) move from the depression into the shallow, slow margins of the stream. As the young fish grow, they move into deeper waters such riffles, runs, and pools, where they have to watch for predators such as raccoons, herons, kingfishers, gulls and crows. Typically steelhead will remain in freshwater for 1 to 4 years before migrating to the sea. If water conditions are right, and the proper cues are received, the young steelhead will move downstream to the estuary where they will remain for a period of time before beginning their oceanic phase.

Restoring Steelhead to Southern California

The key to restoring steelhead to southern California is to provide adequate flows of cool, clean water in our coastal streams, restore habitat on a watershed scale and provide access to historical spawning and rearing areas. This is easier said then done. However, private citizens as well as state and local government are working hard to make this happen. Citizens help through active participation in volunteer stream monitoring and local watershed organizations. City, county and state agencies are working to improve habitat through riparian restoration projects, bank stabilization projects, and finding creative solutions to steelhead barriers. In addition, Southern Californians are voting for initiatives that are good for our communities and the environment.

Want To Know More?

A Guide to California’s Freshwater Fishes. Bob Madgic. Naturegraph Publishers.1999

Field Guide to the Pacific Salmon: including salmon-watching in Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and Northern California. Robert Steelquist. Sasquatch Books. 1992.

Inland Fishes of California. Peter B. Moyle. University of California Press. 2002.

Steelhead Restoration and Management Plan for California. Dennis McEwan and Terry Jackson. California Department of Fish and Game. 1996. Steelhead Restoration and Management Plan for California

Tidewater Goby

Endangered Status:

The tidewater goby was listed as a federally endangered species in 1994. This goby is a small, elongate, grey-brown fish roughly 2 inches in length. It is usually characterized by its large pectoral fins while the pelvic fins are joined below the chest forming an abdominal disc. Male tidewater gobies are nearly transparent and generally remain near the breeding burrows while female tidewater gobies develop darker colors.

Habitat:

Habitat:

This fish is native to California and can typically be found in coastal lagoons, estuaries, and marshes. Tidewater gobies live only in California, and historically ranged from the mouth of the Smith River to northern San Diego County. Though they are still found throughout their historic range, they are at fewer locations, having been extirpated from some sites as a result of drainage, water quality changes, introduced predators, and drought. Through human intervention, this important species may be able to recolonize lost habitat.

Life Cycle:

The tidewater goby typically lives for only 1 year. Reproduction occurs year-round, especially in warmer waters in the southern portion of the species’ range. As breeding commences, males will dig a vertical nesting burrow 10 to 20 centimeters deep in substrate. Female tidewater gobies lay 300 to 500 eggs, which adhere to the walls of the burrow. Male gobies remain in or near the burrows to guard the eggs until they hatch.

For more information on this adorable fish visit: https://www.fws.gov/arcata/es/fish/goby/goby.html

CA Red Legged Frog

Endangered Status:

The California red-legged frog is federally listed as a threatened species throughout its range in California.

Characteristics:

This frog is the largest native frog in the western United States ranging from 1.75 to 5.25 inches from the tip of the snout to the vent. From above, the frog can appear brown, gray, olive, red, or orange, often with a pattern of dark flecks or spots. A cream, white, or orange stripe usually extends along the upper lip from beneath the eye to the rear of the jaw, not to be confused with the Pacific Treefrog which has a black stripe that often extends from its snout across its eye (much like a mask). The undersides are white, usually with patches of bright red or orange on the abdomen and hind legs.

Habitat:

The California red-legged frog has sustained a 70 percent reduction in its geographic range. In southern California, it has essentially disappeared from the Los Angeles area south to the Mexican border.

California red-legged frogs spend most of their lives in and near sheltered backwaters of ponds, marshes, springs, streams, and reservoirs. Deep pools with dense stands of overhanging willows and an intermixed fringe of cattails are considered optimal habitat.

Threats:

Factors associated with declining populations include degradation and loss of its habitat through agriculture, urbanization, mining, overgrazing, recreation, timber harvesting, non-native plants, impoundments, water diversions, degraded water quality, use of pesticides, and introduced predators. Without human intervention this species is at risk of becoming endangered. Recovery objectives include restoring and creating habitat that will be protected and managed, surveying and monitoring populations and conducting research on the biology of and threats to the species and re-establishing populations of the species within its historic range.

For more information visit: https://www.fws.gov/arcata/es/amphibians/crlf/crlf.html

Western Pond Turtle

Endangered Status:

The western pond turtle is a small to medium-sized turtle endemic to the western coast of the US and Mexico. In CA, this speces of turtle is listed as a species of special concern, meaning without intervention this species is at risk of becoming threatened due to declining population numbers.

Characteristics:

The shell of this turtle is usually dark brown or dull olive while the plastron (or underbelly) is yellowish, sometimes with dark blotches in the center. The straight carapace length (length of the shell) is 4.5–8.5 in.

Habitat:

The western pond turtle originally ranged from northern Baja California, Mexico, north to the Puget Sound region of Washington but unfortunately it has lost much of its habitat in Washington (where it is considered endangered) and Oregon (where it is considered sensitive or critical). The western pond turtle occurs in both permanent and intermittent waters, including marshes, streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. It favors habitats with large numbers of emergent logs or boulders, where individuals aggregate to bask. They also bask on top of aquatic vegetation.

In addition to its aquatic habitat, terrestrial habitat is also extremely important for the western pond turtle. Since many intermittent ponds can dry up during summer and fall months along the west coast, especially during times of drought, the western pond turtle can spend upwards of 200 days out of water.

Predators/Threats:

Because of its hard shell, the western pond turtle is generally well protected however, several predators do threaten this species. Raccoons, otters, ospreys, and coyotes are the biggest natural threat to this turtle, and hatchlings have the additional threats of weasels, bullfrogs, non-native crayfish, and large fish. This species is also threatened by humankind with the removal of ponds, wetlands, and contamination of other water sources. This species is vulnerable and at risk of becoming extinct without the continuing efforts of reintroducing this turtle to its native range.

For more informaiton visit: http://www.californiaherps.com/turtles/pages/a.marmorata.html

New Zealand Mudsnails

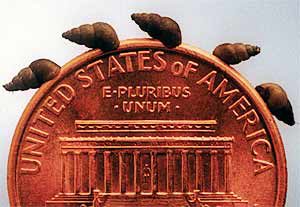

New Zealand Mudsnails can be as small as a grain of sand or up to 1/8 inch. They are typically brown or black.

New Zealand Mudsnails can be as small as a grain of sand or up to 1/8 inch. They are typically brown or black.

WARNING! New Zealand Mudsnails Threaten Native Wildlife

The water that runs through Topanga Creek is the lifeline which fuels the whole ecosystem of our home town, and we are incredibly lucky because it houses so many beautiful native creatures, such as the endangered Southern Steelhead Trout, Arroyo Chub, Western Pond Turtles, Pacific Tree Frog, California Newt, Arboreal Salamander, Western Toad and more. A large part of why this is possible is that we have fewer invasive species living here than have moved into adjacent watersheds throughout Southern California. Unfortunately, after keeping them at bay for nearly 10 years after they were found in nearby waterbodies, the presence of New Zealand Mudsnails in Topanga Creek was confirmed during the summer of 2016. At this time they appear to be blooming in only one segment of the creek about halfway between the bridge and the ocean.

These snails are so tiny that it is very difficult to see them on the soles of boots, on wetsuits or in the cracks in a bicycle tire tread. One snail can reproduce asexually, rapidly infecting a pristine watershed.

What does this mean for the community of Topanga?

We need to take care when we are hiking, swimming, riding, biking and working in the Santa Monica Mountains. When feasible, stay off creek banks and creeks. Do not go from one watershed to the next in one day.

After visiting creeks, go home and remove and scrub all your gear. Dry everything completely for 48 hours. If possible, put any gear that had direct contact with the substrate of the creek in a freezer for a minimum of 4 hours. Otherwise, put clothes, bathing suits and wetsuits in the dryer. Freezing, hot water, or drying treatments are recommended over chemical treatments because they are usually less expensive, more environmentally sound, and possibly less destructive to gear. However, most physical methods require longer treatment times and often cannot be performed in the field.

Keep Topanga beautiful, be sure you are clean of snails before you play in the creek.

Red Swamp Crayfish

Have you seen this creature in your local streams and ponds? The red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarki) is a predator and scavenger with potentially devastating impacts on native amphibian, fish, and invertebrate populations. Like many introduced animals, the red swamp crayfish has no local predators to keep them in check, allowing them to proliferate. Recent studies conducted in the Santa Monica Mountains have linked crayfish to the decline of some of our local amphibians such as the California coastal range newt. Once introduced into our aquatic habitats, red swamp crayfish are very difficult to eradicate. Crayfish are able to burrow down three feet into the mud when water levels are low and are capable of moving on land to find nearby pools. Crayfish are excellent parents, caring for the eggs and young until they have grown to a sufficient size to venture out on their own. It takes less than one year for a crayfish to reach full reproductive maturity. How do these lobster-like creatures make it into our lakes and streams? Unfortunately, we introduce them. Crayfish are popular bait for bass fishermen. They are sold in many fish and tackle shops and are stocked in local lakes as a food source for game fish like large mouth bass and bluegill. However, the problem is not just the local fisherman. The way we live also provides habitat for these creatures. A naturally dry creek is not ideal habitat for a crayfish. By over-watering our lawns and hosing down our streets, we provide the excess flows that crayfish need to survive. Do you have water flowing through your nearby creeks? If you do, crayfish may already be there. Crayfish can be so prolific that you may find fifty of them sitting at the bottom of a deep pool.

Have you seen this creature in your local streams and ponds? The red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarki) is a predator and scavenger with potentially devastating impacts on native amphibian, fish, and invertebrate populations. Like many introduced animals, the red swamp crayfish has no local predators to keep them in check, allowing them to proliferate. Recent studies conducted in the Santa Monica Mountains have linked crayfish to the decline of some of our local amphibians such as the California coastal range newt. Once introduced into our aquatic habitats, red swamp crayfish are very difficult to eradicate. Crayfish are able to burrow down three feet into the mud when water levels are low and are capable of moving on land to find nearby pools. Crayfish are excellent parents, caring for the eggs and young until they have grown to a sufficient size to venture out on their own. It takes less than one year for a crayfish to reach full reproductive maturity. How do these lobster-like creatures make it into our lakes and streams? Unfortunately, we introduce them. Crayfish are popular bait for bass fishermen. They are sold in many fish and tackle shops and are stocked in local lakes as a food source for game fish like large mouth bass and bluegill. However, the problem is not just the local fisherman. The way we live also provides habitat for these creatures. A naturally dry creek is not ideal habitat for a crayfish. By over-watering our lawns and hosing down our streets, we provide the excess flows that crayfish need to survive. Do you have water flowing through your nearby creeks? If you do, crayfish may already be there. Crayfish can be so prolific that you may find fifty of them sitting at the bottom of a deep pool.  The invasive crayfish is just one example of our potential impact on local creeks and streams. Introducing anything into an environment that does not belong there, including pet goldfish and turtles, excess water, pesticides and fertilizers, effects the local plant and animal species that live there.

The invasive crayfish is just one example of our potential impact on local creeks and streams. Introducing anything into an environment that does not belong there, including pet goldfish and turtles, excess water, pesticides and fertilizers, effects the local plant and animal species that live there.